I found the effect amusing, especially when Tertuliano Maximo Afonso engages in tortuous conversations with himself, his alter ego Common Sense or with other people. His chapters are about the usual length, but he writes very long sentences with bountiful commas and very long paragraphs. One day when I have time I’m going to explore what it was that made this discredited political and economic philosophy attractive to Saramago. He was also an atheist and a pessimist, and this aspect of his personality certainly shows through in The Double, though the effect is comic.

There are plenty of intellectuals and writers who were attracted to communism in the 1920s and 30s, but most of them recanted in embarrassment when the excesses of Stalinism became known.

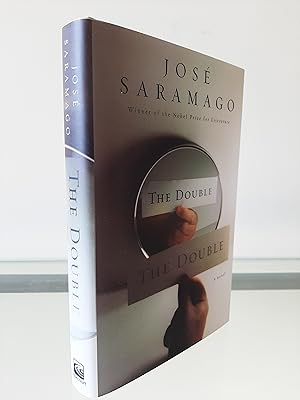

I have vivid memories of the contrast between its warmth, colour and vivacity and the drabness of postwar London.) In Portugal all seemed to be forgiven when Saramago won the Nobel, though the conservative PM who’d supported the religious censorship prudently avoided the mourning when Saramago died.īizarrely, Saramago became a communist in 1969 and remained a member of the party until his death. (Apparently he died at Las Palmas, which I visited as a small child en route to Africa. Wikipedia tells me that he came to the attention of Portuguese censors late in his life, and moved to Spain to avoid interference on religious grounds. Saramago (1922-2010) was a Portuguese author: he wrote novels, plays and journalism and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998. He becomes consumed by anxiety about this double, and his quest to deal with the problem of who owns his identity is, in the hands of this master storyteller, a remarkable story. It’s the story of a most ordinary man, a teacher of history, who one night, watching a video, sees himself as he was five years ago on the screen. The Double, by José Saramago, is very entertaining reading.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)